No.

The recent market reaction to the mini budget has prompted wider discussions about the potentially perlilous state of the UK public finances. In this post I want to provide some clarity on what constitutes a “currency crisis”, and how the typical warning signs help to illuminate the current UK situation.

A currency crisis is routinely used to describe situations where a currency loses a lot of value relatively quickly. However this definition is vague, and when the trigger for quick market movements is a political speech, in the context of a highly polarised and poorly motivated public discourse, it is unhelpful. When I teach my MBA students we use this classic Harvard case and apply the following definition:

A 10% or more fall in the value of a currency, within a week, relative to a suitable external benchmark.

This poses three questions: how much value is lost? over what time period? and relative to what?

Prior to 2016 I told students that by using this definition it is almost impossible to imagine that a currency crisis can occur to a floating exchange rate. When the value of a currency is set by demand and supply, on a competitive market, it would take a ridiculously large shock to prompt such a dramatic and immediate reappraisal. Therefore our discussion in class is focused almost entirely on countries that have some sort of fixed exchange rate, where the crisis is the moment at which authorities abandon their target. In other words, while there are many causes of a currency crisis, the trigger is almost always the abandonment of a fixed exchange rate.

Then, in 2016, we had the results of the Brexit referendum and the UK pound lost more than 10% of its value, relative to the USD in a day. So much for useful rules of thumb!

Some minor quibbles would be at what points we are measuring the rise and fall (i.e. should we only compare an average daily rate, the rate at the end of the trading day, or the most extreme moments within any trading period); and the relevance of the external benchmark. By definition, a fixed exchange rate will have an obvious external benchmark (whether that’s the USD, the Euro, or a clearly defined basket of other currencies). For a floating exchange rate we make a choice.

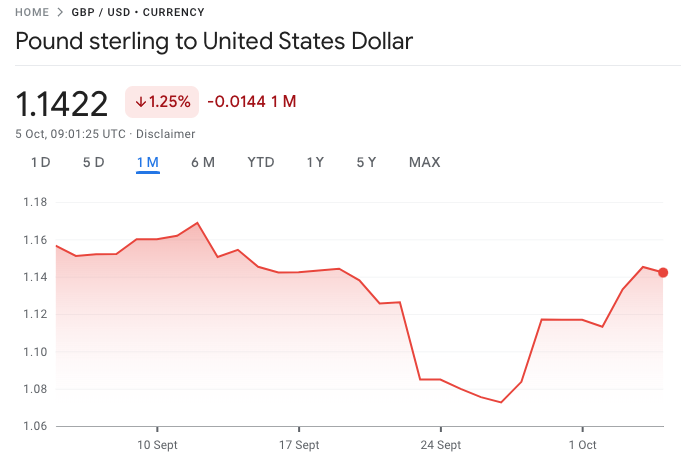

Indeed the danger of focusing too much on the GBP/USD exchange rate is that it can be hard to distinguish between the weakness of the pound and the strength of the dollar. Most currencies have been weakening against the USD and so we aren’t seeing entirely UK news that is influencing that ratio.

I think it’s better to focus on a trade weighted composite index (i.e. the effective exchange rate) and using BIS figures this is what’s happened recently:

The mini budget isn’t a step change here, but if we take the level on Sep 22nd and read through until the trough, which was September 28th, that’s a 4% fall. So no currency crisis.

Having said this, taking the GBP/USD is also sensible, but as Reuters points out this is ~8% fall. So still not a currency crisis.

Of course foreign exchange markets were not the only arena of disturbance, and it’s telling that as the pound has recovered more attention has switched to gilt yields. These are a more useful macroeconomic indicator because they provide a reflection of the premium the UK government is required to pay investors in be willing to buy their sovereign debt. Gilts spiked following the mini budget and it is because of the ramifications that this had to pension companies that prompted the Bank of England to intervene, calming things down.

So I think it’s overblown to call these events a “currency crisis” and would require a clear definition from those who claim otherwise. But this leads us to the main point of this post, which is to consider whether indicators are suggesting that a currency crisis may occur.

The simple answer (Brexit referendum result to one side) is of course not, the GBP is a free floating currency! Indeed the very large price adjustments being made recently reduce the necessity for big swings later. This is the market doing it’s job: rapidly incorporating new information such that single events have less importance. The underlying causes of why a currency is losing its value get incorporated drip by drip, rather than all at once.

That said, we can go back to my MBA classroom discussions and consider the standard list of indicators that might forewarn about an impending currency crisis:

Is the current a/c deficit over 5% off GDP? - when a country imports more than they export they tend to run a current account deficit. For many relatively wealthy countries being a net borrower is no bad thing - it means consumers get access to more products, and we have inflows of foreign investment. A typical rule of thumb is that 5% of GDP amount to a “large” currency account deficit. According to the ONS the current account deficit has been quite volatile recently but most recent data (for 2022 Q2) shows -5.5% (down from -7.2% in Q1). So it’s large, but it’s not deteriorating. Direction can be as important as overall size. I’d say this is flashing orange.

2. How is the current account deficit being financed? - it’s one thing to run a large currency account deficit, but if the predominant source of inward foreign investment (which is being used to finance it) is formed of Foreign Direct Investment (i.e. in fairly large and stable projects like building factories) then there’s little risk of a sudden reversal. By contrast, if the deficit is being funded by portfolio flows, which are prone to sudden reversal, then we’d be more concerned. According to the ONS we can see outflows of portfolio investment but at declining rates over the last few quarters. Inward FDI has been quite stable, and other investment (i.e. short dated bonds) are positive and stable. This looks green to me.

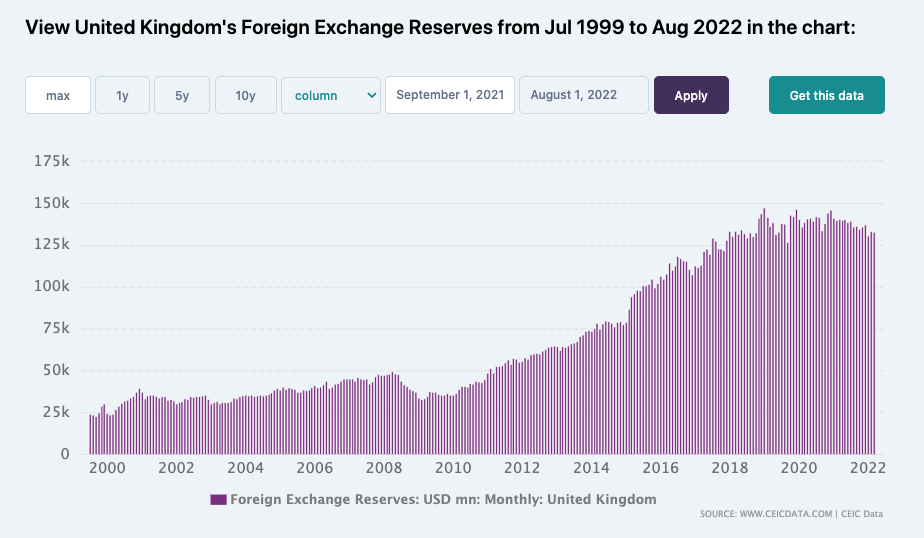

3. How large are reserves? - if sources of inward investment dry up, the key question is whether the government can continue to fund its current account deficit through other means, such as the use of foreign reserves. One of the key indicators that Vladimir Putin was going rogue was his steady stockpiling of international currency, since 2015, reducing dependency on voluntary trade and international cooperation. On the contrary, if a country has a low amount of international reserves, or begins haemorrhaging them, it is a sure sign they are losing control. UK foreign exchange reserves have steadily increased since the global financial crisis, and given that a free floating exchange rate doesn’t require any reserves to manage the stability of the currency, this represents a strong position.

4. Is the real exchange rate deteriorating? - if a country has a fixed exchange rate then it fails to serve as an indicator of impending devaluation, but the real exchange rate will provide more of a clue given that it adjusts for inflation. As shown, an effective exchange rate is a good indicator of general trends, and the trajectory is a concern for the UK. Rather than treat the real exchange rate as indicator, however, we can just look at inflation. The current inflation rate using the traditional CPI basket (which is what the Bank of England use to determine monetary policy) is 9.9%. The CPIH measure, which adjusts for types of housing cost, and is the primary focus presented by the ONS, is 8.6%.

This is obviously way above the target rate of 2% but is subsiding and the general consensus seems to be that the Bank of England are starting to apply the brakes such that it will not remain elevated for long. When using inflation as a predictor of a currency crisis, however, we shouldn’t confuse cause and effect. Rather than viewing the inflation rate as a sign of potential currency deterioration, it is in fact another view of the same problem. While a fall in the exchange rate is measuring the currency against an alternative currency, a rise in inflation is measuring it against a basket of goods and services. These are simply two different ways to revealing the same common issue - a reduction in purchasing power.

5. Is the budget deficit out of control? - According to the ONS, in the first quarter of 2022 the budget deficit was 2.6% of GDP which is smaller than the EU27 average and within the 3% threshold typically deemed to be a red flag. There is a more recent publication, showing a more detailed look at public sector finances, released in September, but I’m not aware of a stable link for a more timely snapshot of the fiscal position. The key issue, of course, is where this is heading. The NIESR forecast the deficit will rise to 8% in 2022/23 and we are still awaiting confirmation of when the OBR’s updated forecasts will be made public. Either way, the deficit is contentious partly because it relies so much on growth projections and what goes into the GDP calculation can have much of an impact on the outlook as any claims about spending relative to tax revenue. For now, however, the warning lights are green.

Public debt rose dramatically during the pandemic and for good reason. Despite recent rises in yields debt isn’t high in comparison to equivalent historical circumstances, and prior to Truss/Kwarteng we’ve all been repeatedly led to believe that debt remains cheap and easy to finance. That can change quickly, but there’s room to manoeuvre.

As a classroom exercise, and looking at publicly available data, there are no clear warning lights indicating an imminent currency crisis. And we should not be surprised - floating exchange rates don’t have currency crises. But the real art is taking more timely, pertinent indicators and anticipating sudden changes in market sentiment. Indeed the main conclusion from my MBA class is that regardless of what data we look at, we can’t reliably predict a currency crisis. So there’s no need to panic. Yet (!)