Richard Murphy is a chartered accountant who has forged an impressive career campaigning for tax reform. He works tirelessly writing punchy blog posts and detailed policy reports. His basic point - that wealthy individuals and deliberately opaque companies find it too easy to evade and avoid HMRC - is surely correct.

I am not a socialist so I am uncomfortable with Murphy's implication that tax is good for its own sake. And I recognise that many experts have cast significant doubt on the validity of his calculations (to which Murphy has responded). Murphy is paid by trade unions, and he's good at what he does. I disagree with his political beliefs, but people like him are important voices in public debate.

I tend to defer to Murphy's judgment when it comes to accounting. But recently he has emerged as an economic commentator. As the self-styled originator of the concept of "People's Quantitative Easing" (PQE), and having been said to have influenced Jeremy Corbyn's economic platform, Murphy's profile has risen significantly. This concerns me greatly. I believe that PQE is economically illiterate and potentially very dangerous.*

I am an academic economist that specialises in monetary theory. I have no political loyalties and am generally sympathetic towards Jeremy Corbyn's character and motivations. But we need a reasoned debate about PQE, and one would think that the person claiming credit for creating it would be involved.

This article is not intended to provide a critique of PQE (although I've tried to explain my general opposition in the footnote). My issue now is Richard Murphy's hostility to open debate.

I was interested to watch Murphy's recent interview with Andrew Neil on the Daily Politics (permanent link):

In it, he makes the case for "modest amounts of inflation" and rests it on the fact that Mark Carney is currently failing to meet his 2% inflation target. (Note that Murphy is incorrect to say that Carney's inflation target is 2%. Inflation is not supposed to always be on target, but to meet that target "within a reasonable time period". Therefore technically Carney should be judged based on whether he is keeping inflation expectations at 2%, not on last months actual data. This seems like a pedantic distinction, and I'm sure I've glossed over the difference myself at times. But it's something that a supposed economic advisor should know).

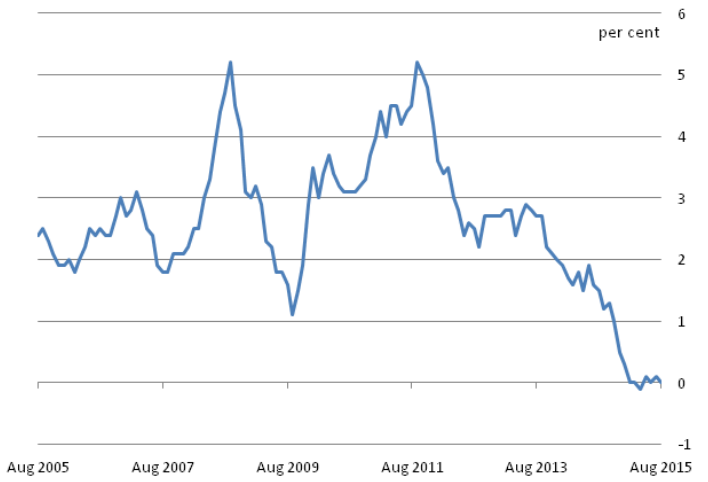

This presents an interesting issue, because for much of 2011 inflation was well above 2%.

Many economic commentators at the time were saying that this inflation was temporary, and driven by supply side factors. In such circumstances, tolerating inflation is a better option than the Bank of England raising interest rates to slow down the economy. In such circumstances the fact that real GDP growth was low may be more important than inflation being high. So I understand that there is a case for the Bank of England to increase QE (i.e. boost aggregate demand) in 2011.

Let me emphasise that the concern about PQE is that it would be used excessively, and in doing so would contribute to inflation. The whole issue is whether we can trust that PQE will not be abused. Murphy attempts to downplay this fear by claiming that he wants "modest" PQE, and that it's a good idea because inflation is under target. But if Murphy's reasons for advocating PQE circa 2015 are sincere, this implies that he did not think there was a case for PQE in 2011. My recollection is that he has been advocating PQE throughout this time period, even when inflation was above target. So this is a question I posed to him, on his blog, and our subsequent exchange:

Given that he's previously blocked me on Twitter, and deleted my comments, I am not surprised by how that exchange concluded. I am frustrated, because I believe that there's an inconsistency in his argument and he's unwilling to clarify it. And indeed he's even unwilling to permit a courteous discussion between commentators. For example "Bob" left the following reply to my comment:

But my response to that was deleted (here is a screenshot before it was deleted):

Maybe Bob was right. I was keen to hear his response.

So I am frustrated. But I am also annoyed because this is a serious issue and Murphy has a responsibility to engage with the economics community. Whilst he was a blogging accountant it was ok to disparage the whole of the economics profession as being deluded ideologues. As a heterodox economist myself, and critical of the neoclassical orthodoxy, I sympathised with him! But if he wants the attention that comes with being Corbyn's economic "guru" and the respect that comes with being an "academic" he needs to be intellectually mature.

This isn't about abuse or even civility. It's simply a refusal to engage in debate, and an attempt to shut down questions that are perceived to be challenging. Most of the economists I know would dismiss the likes of Richard Murphy as being self-evidently wrong. But when those of us who do try to engage with the sustance of the ideas get insulted, blocked and deleted, it is a real shame.

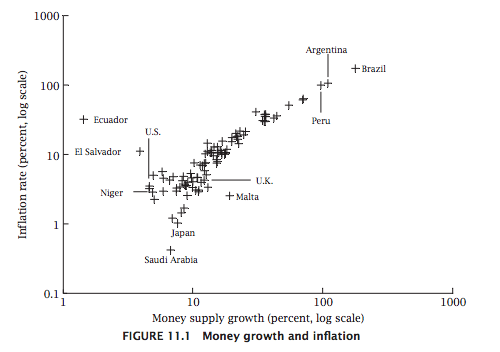

* One of the few things that macroeconomists actually agree on is that hyperinflation is the result of excessive money creation. This is as close to an empirical fact that macroeconomics can deliver - see David Romer's standard textbook, "Advanced Macroeconomics":

And we have a very strong understanding of the reasons why money creation can become excessive - when governments resort to the printing press to cover their fiscal ill-discipline. The catrostrophic monetary events of modern times (whether it's Weimar Germany, Yugoslavia, or Mugabe's Zimbabwe) happen when people become blase about the link between public spending and the money supply.

Back in 1997, when New Labour were keen to build their economic credibility, Gordon Brown made the Bank of England operationally independent. This was in line with a general trend in the 1980s and 1990s to separate fiscal policy and monetary policy, by outsourcing the latter to the central banks. When quantitative easing (QE) was initiated in 2009, economists like myself were concerned that it would weaken the independance of the Bank of England. In many ways the emergence of PQE as a potential tool is our worst nightmare, and reason enough to have opposed QE in the first place.

If you want more detail on how to understand monetary economics, I have written a textbook that explains it to non economists. Richard Murphy should read it.